Joseph Brooks and his boyfriend Henry moved to Northern California in the mid-1970s in search of new music and a scene.

San Francisco had become a mecca for underground queer performance groups like The Cockettes and Angels of Light. Born out of the Kaliflower commune in Haight-Ashbury, they blended hippiedom and rock and roll with “genderfuck” transgression.

After the group split in 1972, various members decamped to New York, Seattle, or Los Angeles. Tomata du Plenty and Gorilla Rose created the radical drag troupe Ze Whiz Kidz in Seattle. They later joined fellow Cockette Fayette Hauser in New York to perform comedy shows with the Ramones and a pre-Blondie Debbie Harry.

Artists were starting bands, musicians were doing performance art, and gender was fluid. It all fit loosely under the umbrella of punk.

So when the Sex Pistols went on their first and only US tour, Joseph and Henry were there to see the band’s last show at Winterland Ballroom in San Francisco. The entire West Coast scene had convened to see the incendiary band, and unbeknownst to the fans, it would be the Pistols’ final performance. “Ever get the feeling you’ve been cheated? Good night,” snarled Johnny Rotten, as he walked off the stage.

Joseph and Henry bonded that weekend with a group of fans from Los Angeles, who were starting bands, organizing shows, dressing up, and opening up shops on a small strip of Melrose Avenue in Hollywood. It was the beginnings of the California punk scene.

I first learned about the Melrose scene while making my Pee-wee Herman documentary (which is coming out next year). Paul Reubens conceived of his alter ego at The Groundlings improv comedy workshop next door to the iconic punk record store Vinyl Fetish. When I showed my friend Matt Connors some archival footage of Pee-wee in the record store, he said, “Did you know my friend Amra’s dad Joseph was the owner?”

Today Joseph Brooks is an accomplished jeweler and an avid bird watcher. When we spoke on the phone recently, I learned how instrumental he and his then boyfriend Henry Peck were in bringing groundbreaking English music to the States.

Back in 1977, when Joseph and Henry were getting into punk, they took a trip to London to meet their favorite musicians– it was as simple as that. When they returned home with a haul of English records, they decided the best way to channel their anglophilia was to open a record store in Los Angeles where the punk scene was taking off.

Joseph and Henry couldn't afford a storefront on Melrose, but they found a modest space around the corner on La Brea. They didn’t have enough money to buy a crate of records, but nonetheless, they called their new store Vinyl Fetish.

In the center of the space, Joseph and Henry hung large plexiglass panels to exhibit the fronts and backs of the handful of rarefied LPs they carried home from England. They were fittingly fetishized like works of art.

At night, Joseph and Henry took down their floating plexiglass displays to make room for film screenings and performances. One notable act was Johanna Went. She would create tableau set pieces with found objects, murmur or scream incomprehensible lyrics, and spout fake blood.

A year after opening Vinyl Fetish, Joseph and Henry still only stocked 50 import records. But when the premiere punk band of the LA scene, X, had their first record release signing at the store, it became a destination.

Joseph and Henry started inviting then unknown bands from the UK like Cabaret Voltaire and the Psychedelic Furs to do record release events at the store. Eventually English record distributors asked them to host new bands coming through town. When U2 had their record signing at Vinyl Fetish, twenty people showed up.

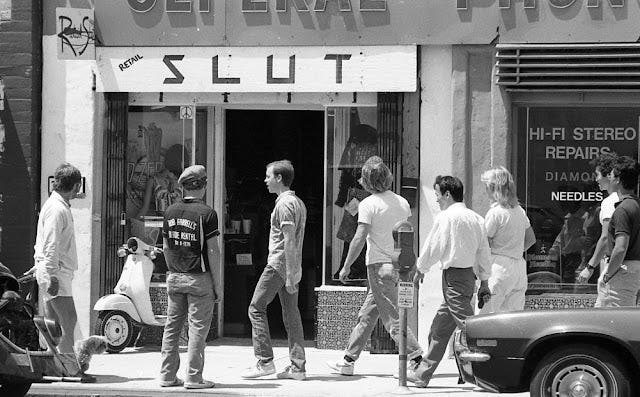

The owner of an English import clothing shop on Melrose told Joseph and Henry about a vacant storefront across the street, and they signed a lease. Vinyl Fetish finally had enough inventory to be on Melrose, and in the early 1980s, a crop of other punk and new wave businesses started opening on what became a subcultural strip. There was Neo80, Flip of Hollywood, Retail Slut, l.a.Eyeworks, and eventually many more.

Between classes and performances at The Groundlings, Paul Reubens would wander around Melrose and peruse retro toys at Wacko, hangout with the cool lesbian owners Barbara and Gai of l.a.Eyeworks, and take stock of the new album art at Vinyl Fetish. He started to notice record covers and posters that he loved behind the plexiglass displays, all by the same artist named Gary Panter.

Gary had been an art student in Texas, and he started his own Devo-esque performance art group called Apeweek. He was unaware of any art or music scenes of particular notoriety in California, but he followed a girlfriend to Los Angeles.

When Gary came across a copy of Slash magazine on a Melrose newsstand, he scoffed at the crummy artwork being used to promote the underground bands. He thought maybe his illustrations could fit into that niche, and before long, he was drawing album covers for bands and musicians like The Plugz, Frank Zappa, and creating his own cult comic called Jimbo. Gary quickly became the premiere artist of the California punk movement.

When Paul approached Gary to make a poster for his new midnight play called The Pee-wee Herman Show at The Groundlings, Gary offered to design the entire set and its puppets. The incredible success of that show and its titular character would lead to the pair’s collaboration on the children’s television show Pee-wee’s Playhouse.

It was a fertile moment in Los Angeles with a plethora of art school students exploding traditional mediums, influential British bands coming through town to perform in makeshift clubs, and an alternative comedy scene percolating alongside musicians and artists.

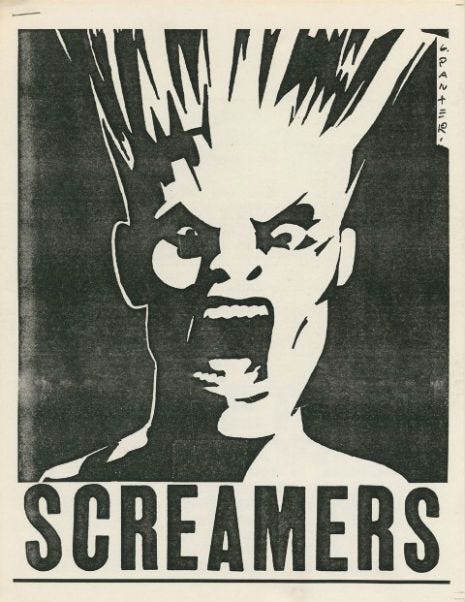

Years ago, my friend and collaborator Jon Savage– the author of the definitive punk history England’s Dreaming and the newly published queer music book The Secret Public– played me a video of the legendary LA punk band The Screamers. They were fronted by the former Cockette Tomata du Plenty, and immortalized in Gary Panter’s block print style artwork.

Everybody looked up to Tomata, and according to Joseph, he was the undisputed mayor of the LA punk scene. After leaving the Cockettes with stints in Seattle and New York, Tomata moved into a ramshackle craftsman duplex on Wilton and Los Feliz Boulevard. People in the punk scene called it Wilton Hilton, and when a band came through Los Angeles, they stayed with Tomata and his roommates, who hosted epic house parties.

Joseph remembers going to Wilton Hilton during his first weeks in LA to meet the Ramones and Blondie. Tomata grabbed him by the hand, and introduced him to every guest at the party. He was a bit older than others in the scene, and as its boyish statesman, he wanted everybody to know each other, or to at least feel welcomed.

In the Screamers, Tomata found underground fame with his tightly wound synth-punk performances. The band never released a record, but their legacy now lives on YouTube. Jon Savage best describes the video he first showed me of Tomata:

His background in performance art gives him total control: his sculpted, swept-up 50s psycho hustler face keeps firmly within the camera position, lapsing from anger into stillness in the space of seconds. He is simultaneously within and outside the song: this is not arch, but conversely even more involving.

Besides turning me on to The Screamers, Jon also gave me a copy of John Rechy’s 1967 Los Angeles gay noir novel Numbers. The book follows a hustler’s return to Griffith Park, where his unrelenting pursuit of sexual conquests leads to his unraveling. Soft Cell’s song Numbers is inspired by the book, and Lou Reed was an enormous fan of Rechy and his other gay LA masterpiece City of Night.

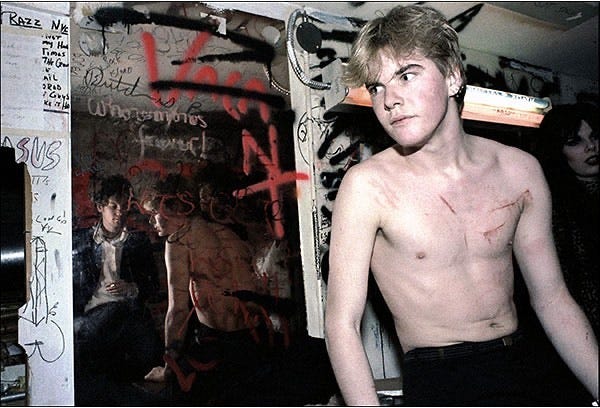

From Rechy to DuPlenty, there was a continuum of underground queer art being produced in Los Angeles, and Joseph found himself in that small circle. He remembers going to gay bars with the punk icon Darby Crash from the Germs. “Hardcore kids at the time would have been in disbelief to learn that their hero Darby was queer,” Joseph told me.

Shortly after Vinyl Fetish opened on Melrose, the scene exploded. Joseph and Henry now had enough money to stock rows of wooden bins with records. Twice a week, British distributors would call the store with their new titles, and if Joseph hadn’t heard of a band, he’d buy one record for himself and another for the shop.

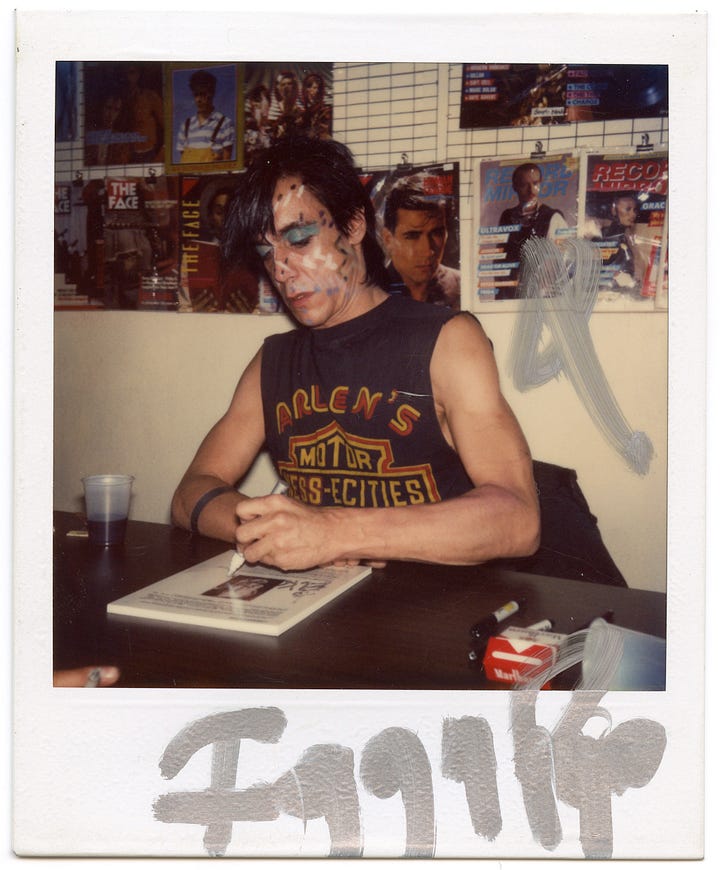

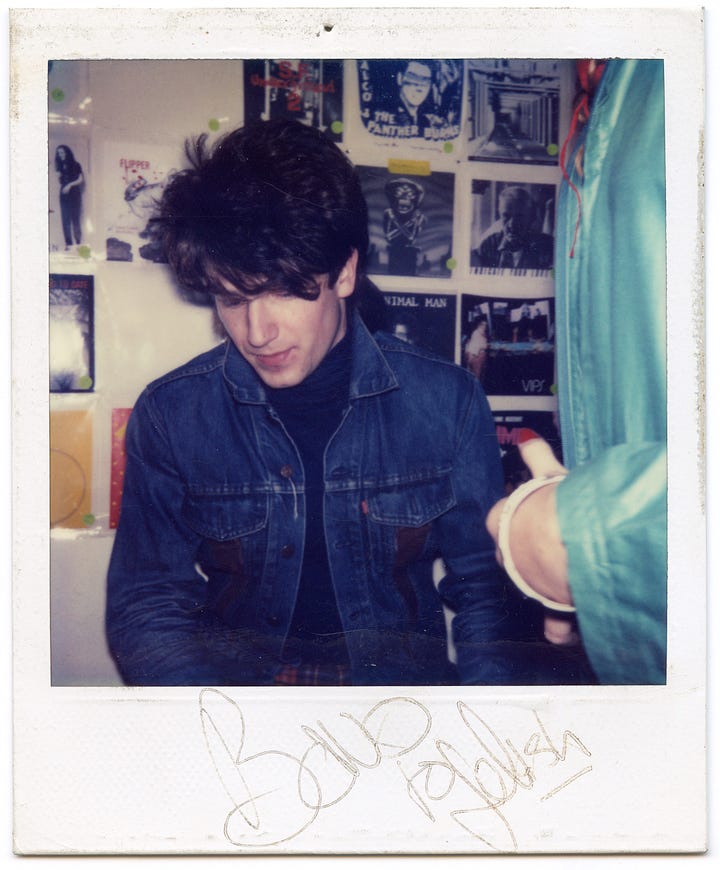

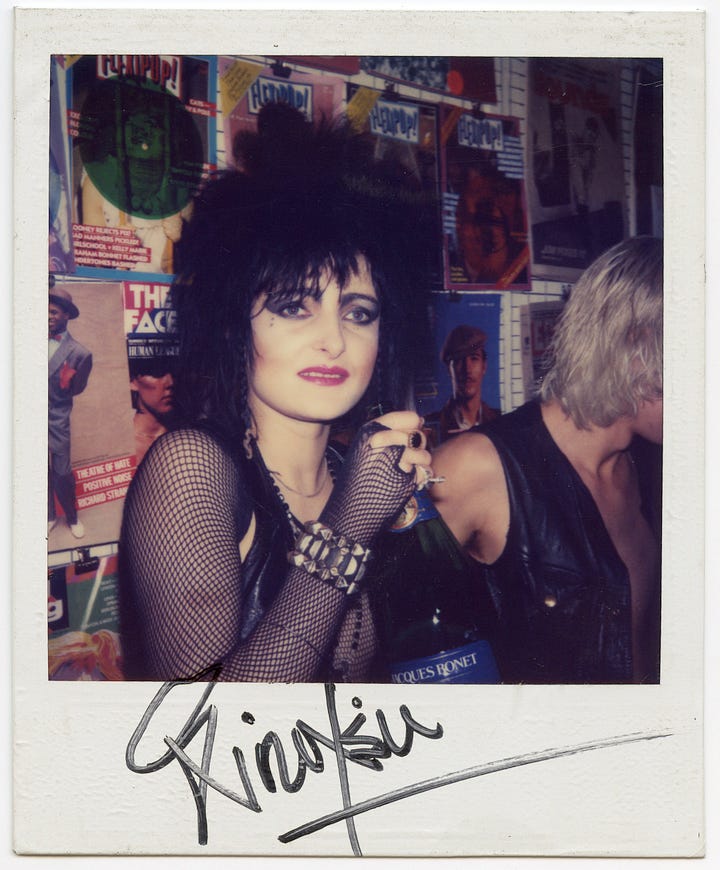

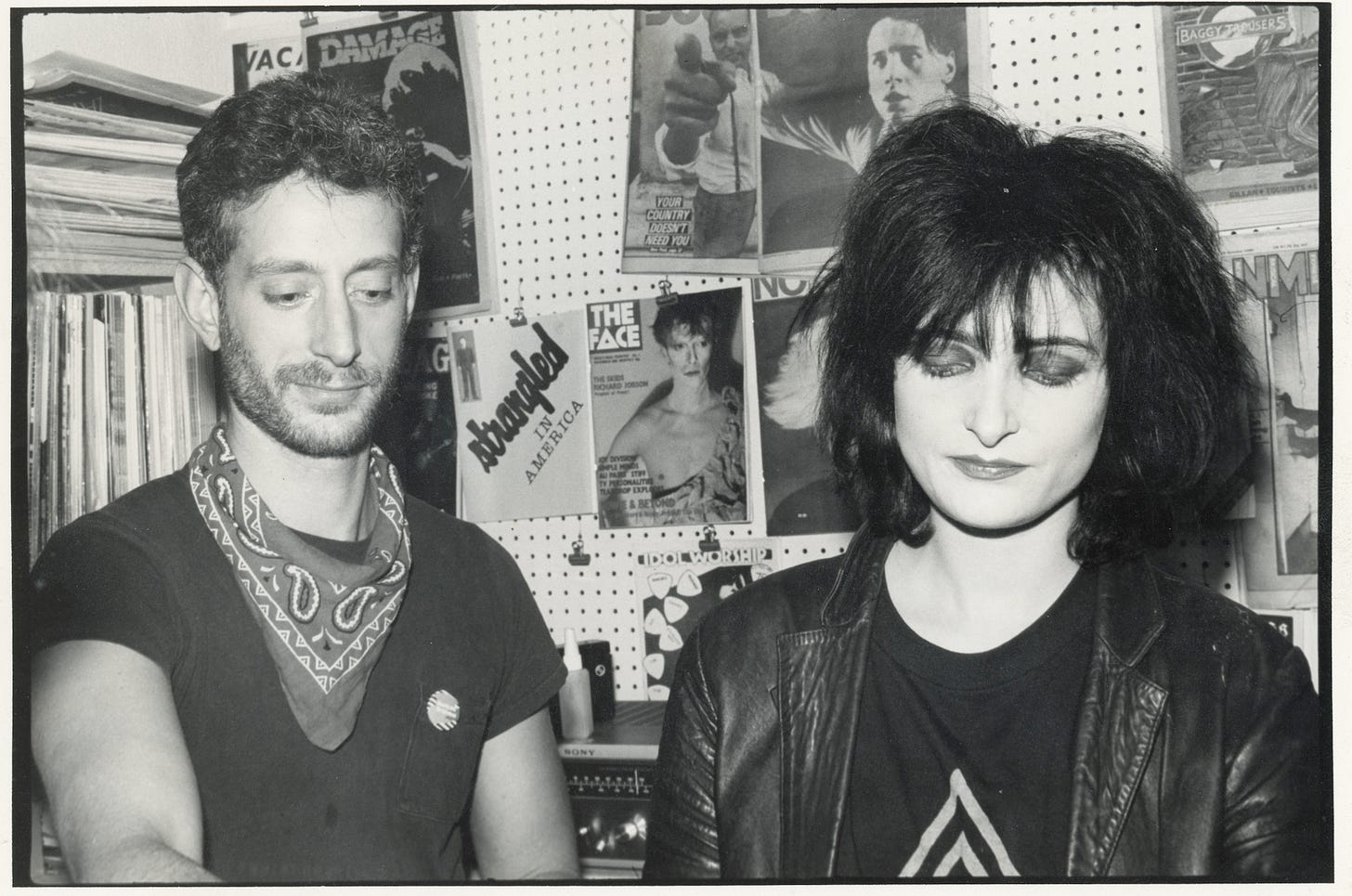

Joseph and Henry were becoming tastemakers in the scene, and the influential KROQ radio station gave them a Monday night “import” show to debut new music from obscure bands like Duran Duran, Depeche Mode, The Smiths, Bauhaus, and Culture Club. Those bands would all come through Vinyl Fetish for record release events. Siouxsie and the Banshees, Iggy Pop, the Misfits, Joey Ramone, Soft Cell, and more followed.

When the New Romantic scene took hold in London, Joseph and Henry also became the primary DJs in LA of the new electro music. They could rent a space like the Ukrainian Cultural Center for virtually free. When they hosted a Bauhaus night, Joseph and Henry stole coffins from the dumpsters at Forest Lawn cemetery, put people inside of them at the club, and scattered dead flower arrangements across the dance floor.

Legions of punk kids would congregate outside Vinyl Fetish panhandling and trading fanzines. The store was filled with their xeroxed flyers—the primary mode of communication in the expanding scene.

One day a kid named Izzy gave Joseph a flier for his show, and handed him a cassette tape of his band. Joseph liked the music, and shared it with a friend at a record company, which got the group their first deal. They were called Guns N' Roses.

The music was changing, and so was the atmosphere on Melrose. Parents would drive their kids into the city for the day and dump them in front of Vinyl Fetish. Joseph saw busloads of what he describes as “boneheads and surfers” coming to Melrose from Orange County.

Skinheads were taking over the shows, and what started as a heavily queer, artist-driven community became overrun with adolescent male aggression. The venues became skittish about booking punk shows because they didn’t want damage and trouble. Joseph said, “The scene became, you know, like a bunch of these idiot surfer homophobes coming to pick fights. Fuck that.”

After hosting legendary club nights and becoming an ambassador for groundbreaking musicians, Joseph wasn’t really interested in sitting behind a counter anymore. So in 1986, he and Henry sold the store and the name Vinyl Fetish, and they moved on.

Tomata also dropped out of the punk scene around that time too, and he turned his attention to visual art. He painted watercolor portraits of his favorite poets, TV stars, and country singers; directed performance art productions, and was the art critic on the cable television series, What's Bubbling Underground.

In search of a new scene outside of the hype of Melrose, Tomata moved to Miami’s South Beach— then a crumbling art deco paradise for elderly Jewish retirees. He had exhibits in bars, small galleries, and even at a laundromat, where he sold his paintings for 10 to 25 dollars. To make ends meet, he swept up bottles at The Deuce Bar.

Until the end of his life in New Orleans, Tomata was proud of his status as an outsider artist. In this poignant CNN segment, he shows off his latest painting of Lucille Ball, and he’s celebrated at an exhibition with high praise from Exene Cervenka of the band X and Jane Wiedlin from The Go-Go’s.

He died of cancer one year later in San Francisco at the age of 52.

This history reminds me of my friend Will Munro, who was an underground fixture in Toronto in the early 2000s. His legendary club night Vazaleen was a hub for the latter day queer punk scene. As a DJ and artist, Will brought major talent through Toronto like Nina Hagen and The Gossip, and he also provided a hometown venue for Canadian groups like The Hidden Cameras, Lesbians on Ecstasy, and Peaches.

Will sadly died far too young from brain cancer in 2010.

There is a sentiment amongst people my age and older that the halcyon days of underground music being shared through record stores, house parties, clubs, and magazines is over. Culture isn’t the same, of course, but I’m sure similar or new modes of transmission are thriving. I do believe that fandom is an enduring force that brings people together for brief but potent moments of ingenuity and community. There are certainly new Vinyl Fetishes in one form or another.

It’s been a while since Joseph revisited his Vinyl Fetish days, and fortunately for us, he was willing to crack open his vault of polaroids. Thank you to Joseph for sharing these images and stories, and thanks to Jack Wiegmann for scanning them.

My sister was friends with the guy in the knit sweater with Peewee and Henry (also shown in the documentary) Jeffrey or Geoffrey. Does anyone know his whereabouts now or his last name?

I remember being 16 and taking the Visage record off the shelf. I had Steve Strange sign it and walked out without paying. It felt like a little retribution for the bully gatekeeper vibe Joseph and Henry wreaked on the exploratory kids who’d frequent the shop looking for answers. They didn’t make it easy for us. Love that store.