Every summer there’s a convening of documentary filmmakers, students, and academics called The Robert Flaherty Seminar, named after the pioneering director of the early documentary Nanook of the North. At “Flaherty,” as it’s now called, you attend three daily film programs, followed by exhaustive Q&As with filmmakers that are sometimes enlightening, but often quite grating and needlessly confrontational. I attended twice as a film student, and on my first night, I met two longtime friends, the film programmer and writer Ed Halter and the documentary filmmaker Sam Green. They got me very stoned, and the rest is history.

Five years ago, Sam and I were rowing in a boat with the tourists at Central Park, and he said, “You’re now the age I was (35) when I met you at 19.” I replied, “I must have been pretty annoying,” and he confirmed, “You’re exactly the same.” Back then, I was very impressed by Sam—a semitic heterosexual heartthrob living in San Francisco— who was in production on what would become his seminal documentary The Weather Underground. He became a sort of filmmaking big brother to me.

One thing I appreciate about Sam is that he dispenses film ideas with no strings attached. Most filmmakers are proprietary over stories because they operate from a place of creative scarcity. Sam does not. He writes a lot of ideas on his hand throughout the day, and on multiple occasions, he has pitched me great ideas for films that I should direct. Just the other day, he sent me a voice memo that said, “My friend was talking about driving cross-country in the ‘90s listening to Kitty Kelley’s unauthorized Nancy Regan book. You should make a Kitty Kelley doc—imagine the tapes!” For those that don’t know (I did not), Kelley is a critically reviled and hugely popular unauthorized biographer, who drops major bombs about her famous subjects from questionable sources. In other words, she’s a high profile star fucker and a consummate gossip.

Sam’s message reminded me of another great film idea he once gave me— a documentary about the other Sam Green. Like Kelley, that Sam Green was a prolific social climber, operating at the highest echelons of New York society. He’s best known for opportunistically recording countless hours of phone calls with Greta Garbo in the latter part of her reclusive life. After Sam told me about the Garbo phone recordings, I contacted Wesleyan’s Special Collections library, where at the time, the tapes were stored under lock and key. There’s nothing I love more than a forbidden archive.

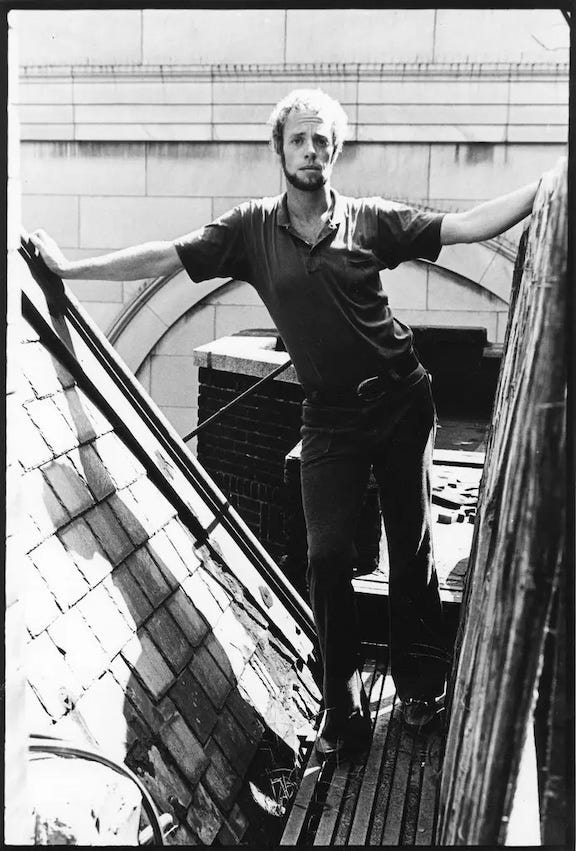

In his obituary, The New York Times called Sam Green “a collector of people who approached the wealthy and famous with the ardor of a lepidopterist wielding a butterfly net.” Some of Green’s butterflies included Andy Warhol, his superstar Candy Darling, the legendary photographer Cecil Beaton, and he was even appointed the guardian to Sean Lennon if John and Yoko were to pass away. Green had grown up surrounded by art in a family of academics (his father was the Dean of the fine art school at Wesleyan). However, Green self-fashioned a blue-blooded origin story, claiming to be the heir of a founding father and two presidents.

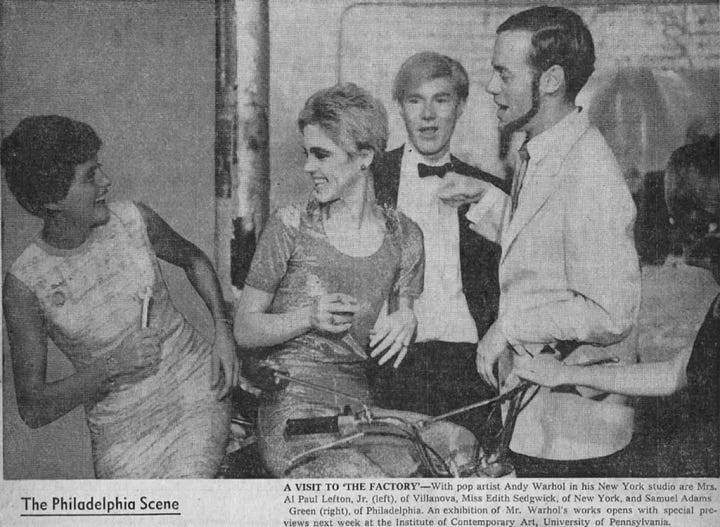

Green was also bisexual and attractive, and he made good use of his sexual versatility. When he met a young and unknown Andy Warhol, Green organized the artist’s first retrospective at the ICA Philadelphia, a museum where he was appointed director at the age of 25. For Warhol’s opening, Green invited some 6,000 guests to a gallery with a capacity of 300. That happening became a pivotal moment in 1960s underground culture, and helped precipitate the explosion of Pop Art in the mainstream. (The pandemonium of the opening is brilliantly recounted in Jean Stein’s masterpiece Edie.)

In the end, it was the social dimension of the art world that enthralled Green. While he very well could have become a respected institutional curator in the footsteps of his scholarly father, Green instead became a gifted social climber. His acquaintance John Richardson said in the Times, “In his social life, he was straight, and he had to be straight, because he lived off very rich, somewhat damaged, women. You’d visit some rather vulnerable older grande-dame and there, of course, was Sam. Somehow he’d got in.” Enter Greta Garbo.

Garbo had defined what we think of as the Golden Age of Hollywood, first as a silent film star, and then as a major MGM icon in the 1930s. But in 1941, her performance in George Cukor’s Two-Faced Woman was critically panned, and at the age of 36 after performing in 27 feature films in the span of 16 years, Garbo abruptly retired. She called the film “my grave.” For the next 50 years, she lived in New York, going on daily walks and averting tourists and photographers, who she called “customers.” She once said, “I don’t have to live in New York… I could live in hell.”

According to Robert Gottlieb’s biography Garbo, her daily routine consisted of eating toast in front of the black-and-white TV in her bedroom (she said she couldn’t “stand the bother” of buying a color television), going shopping for groceries, resting at home, going out again for an afternoon walk, and returning by 5:30 for dinner on a tray in front of the TV. Asked about her plans for the day, she once said, “I don’t know. I walk. That’s what I’m doing. I walk.” Sounds good to me!

There were multiple queer men competing to be Garbo’s “walker.” Photographer, designer, and opportunistic bisexual Cecil Beaton boasted that he was the only man who ever physically satisfied Garbo (corroborated by Tennessee Williams, who wouldn’t know). But Sam Green told Garbo’s biographer Hugo Vickers that Beaton was “too star-struck to star-fuck.” Touché.

Green first laid eyes on Garbo at her birthday party on September 18, 1970. He was 30, and she was 65. Green said about their first meeting, “I knew little and cared less about Garbo, and I'd never seen any of her films.” Classic star fucker move: I didn’t even know she was famous, we just clicked! The whole meeting was engineered by the aristocrat Cecile de Rothschild in Saint Raphael on the Riviera. She had spent two years observing Green on her yacht, assessing if he would be a suitable companion for an increasingly isolated Garbo.

Back in New York, Green and Garbo were reintroduced at the Regency Hotel by Rothschild. As Green walked Garbo home, she said, “I should stick with you. I haven't had a laugh like this in years.” A legendary friendship was born, and in the years that followed, they met twice weekly to go on leisurely walks through the city. In Central Park, Garbo would often hug her favorite trees.

Early on, Green told Garbo that as an “art dealer working from home,” he routinely recorded his phone conversations. Garbo puzzlingly took no issue with that, as long as the recordings would never be exploited during or after her lifetime. Each time that Green called, Claire Koger, Garbo's maid, would pick up the phone and say nothing. Green would identify himself, and Garbo gave Koger either the thumbs-up or thumbs-down sign. Over the course of their 15 year friendship, Green recorded over 100 hours of phone calls with Garbo.

In their conversations, Garbo often spoke of herself with male pronouns. “I have been smoking since I was a small boy,” she once said. Green believed her gender play was a psychological exercise to transform into another person, especially when she begrudgingly recalled her times in Hollywood. Today we’d speculate that she was gender queer. Garbo said to Green once, “I'm kept woman but somebody missed a good man in me.”

One afternoon Green was visiting Garbo at her apartment, and she was in the kitchen preparing Cutty Sark cocktails. When Green dropped a peanut on the floor, he reached under the couch, and felt the synthetic hair of a small troll doll (the collectible kind with fluorescent hair). When he knelt down to look beneath the couch, he discovered an array of troll dolls, carefully arranged in a vignette, like a little family. Each time he came to visit, he’d check on the trolls when Garbo was in the other room.

Then after 15 years of friendship, things between Garbo and Green soured. A writer from the tabloid Globe called Green’s assistant, who spoke out of turn and dished everything he knew about their friendship. The cover story headline that followed read, “GRETA GARBO TO WED AT 80… Bridegroom will be art dealer 30 years her junior.” Green had been gallivanting through South America and had no idea about the salacious publicity. When he returned and made his regular call to Garbo, she said, “Mr. Green, you've done a terrible thing.” Green said sheepishly, “Does this mean we're not speaking anymore?” She replied, “Right.” He pleaded, “Is there nothing at all I can do to make this right?” “Yes,” she said, “hang up.”

That was the last time Sam Green spoke to Greta Garbo. In 1985, she was told that he had played a recording of one of their phone conversations at a party. Green emphatically denied this: “I would never exploit her. God knows I had a thousand opportunities.” That said, Green went on to speak about his friendship with Garbo in a 2005 Biography Channel documentary, and there are some gems in this interview from the Daily Record.

Sam Green’s story makes me wonder what the goals are for a professional social climber. I went to college with Derek Blasberg, who today is a latter day Green. His instagram (which has 1.6 million followers) is littered with every conceivable starlet on his arm, and he moonlights as a consultant for Gagosian gallery, where he recently curated a star-studded Avedon retrospective. Green called this rarefied profession “social work.” He was a secret keeper, until he wasn’t.

After his halcyon days in New York, and as his social circle diminished, Green moved to Massachusetts and pursued his own quasi-aristocratic venture. Through his Landmarks Foundation, he cobbled together capital to preserve sacred sites around the world. You could call him an old-fashioned colonialist, or an appreciator of fading cultural treasures. Green said, “The work I do now is not a reaction against a life spent mixing with the rich, it is a continuation of it. I put all the contacts I have made in my career to good use.”

Many years ago, the filmmaker Sam Green did a lecture at The New School. Sam called the school to collect his meager honorarium (they take literally months to pay you), but he was informed that the check was sent to another Sam Green at an address on the Upper East Side. It had already been cashed. A strange yet unsurprising coda to this story— the other Sam Green was a mooch. He died in 2011 at the age of 71.

Had the story of The Garbo Tapes been told at the Flaherty Seminar, there would surely be hours of debate about documentary ethics. While ethics are a necessary foundation for our work, I’m personally more inclined to think about the documentarian’s responsibility to be “fair” to subjects. Was it fair that Green created an unprecedented archive of Garbo in her recluse years? It was consensual and largely mundane. I think it’s unfair to assume that Garbo’s eccentricities were symptoms of mental illness, or that her lifestyle was born from loneliness. She had agency and predilections, and perhaps in some unresolved way, she wanted that to be known. Regardless of the ethical murkiness behind Green’s recording, I do not believe that his tapes should be destroyed.

A few weeks ago, my Sam Green connected me to an archivist at the Beineke Library at Yale University (without a doubt the most beautiful library that I’ve ever had the pleasure of researching in). I was looking for untapped film archives, and while surveying their collections, the archivist mentioned that they have the other Sam Green’s papers. In a surprise twist, Yale has digitized all of the tapes, except for two that were found blank. While they can’t be duplicated because of copyright restrictions, anybody is free to sit in the ethereal reading room and to listen for hundreds of hours.

Who wants to go to New Haven?

I do!

I almost missed this one! You are a font of fascinating information. I cannot wait for the next one. Thank you.