In December of 1979, 14-year-old Robert Ben Madison was killing time before Christmas break at the Downtown Milwaukee library branch. That’s where he spent most of his time to avoid, what he called, "the violent, snowball-throwing mobs of sport-infested youth.”

Each day after school, Ben poured through books about politics and history, he learned about utopian societies, and drafted his own disaffected manifestos. He was imagining a new world, free from the “thuggism, vandalism, fundamentalism, and the sort of me-first anarchy” of high school.

Ben couldn’t change Milwaukee, and at that young age, he certainly couldn’t leave it. So the only logical choice was to secede.

In the days leading up to Christmas, Ben devised a plan: he’d declare his bedroom a sovereign state called The Kingdom of Talossa. (“Talossa” being Finnish for “inside the house.”)

Ben put on his favorite Fleetwood Mac song “Tusk,” and he declared it the national anthem. Next he stitched together bands of red, green, and white fabric to create a makeshift flag (red to symbolize tenacity and green for monarchy). He rifled through his closet and pulled out his debate team suit, and he put on a Milwaukee fire department hat he bought at the used bookstore.

Family and neighborhood friends gathered in Ben’s living room as he descended the staircase to deliver a speech. On December 26th at 7pm, Ben issued a Declaration of Independence. He officially seceded from the United States to become his Royal Majesty King Robert I of The Kingdom of Talossa.

In 2000, Ben was 34-years-old and still living in his childhood bedroom kingdom. He had recently dropped out of a Ph.D program in History to pursue his high school teaching certification. In the late 1990s, a new movement of “micronations” had emerged on the Internet, and a journalist from Wired magazine made a pilgrimage to Ben’s legendary bedroom to report on the phenomena.

Ben, of course, had thoroughly archived his royal records, and he pulled down a cardboard filing box for the journalist to examine. Inside there was a schematic drawing of the bedroom: The Kingdom of Talossa stretches from the record player to the bookshelf; the bed is one province, and his desk another. The southwest corner of the country is a region called Vaate-Komero (Ben’s closet). A subsequent royal initiative called "Outline of T.L.R.P. (the Talossan Land Reclamation Program)” describes Ben’s plan to clean his room.

That night, the journalist delved into Ben’s 270-page tome The History of The Kingdom of Talossa Volume 1: The First Decade. He was surprised by a significant detail in the chapter “Freshman Year, 1978-1979.” After discussing a formative trip to Europe in exhaustive detail, Ben unceremoniously mentions his mother’s death:

February saw tragedy with the death of Ben Madison's mother, who died in her sleep of unknown causes. The family met to discuss the future, and it was decided to put the event behind them, and not get bogged down in sentimentalities. It was an event that gave young Ben his first experience with death, and he learned that a strong will was the only way to respond.

The next day when the writer asked Ben about his mom, he said abruptly, “I got over it pretty quickly. It didn’t really affect me that much.”

Some precocious teenagers might have been content to declare their independence and to make a flag. Ben, however, escaped much deeper into his imaginary world when he invented El glheþ Talossan, an official language for Talossa. Ben had nobody to converse with in Talossan (tellingly the word “Fieschada” means “love at first sight”), but nonetheless, he developed an elaborate vocabulary that came to include some 35,000 root and 121,000 derived words.

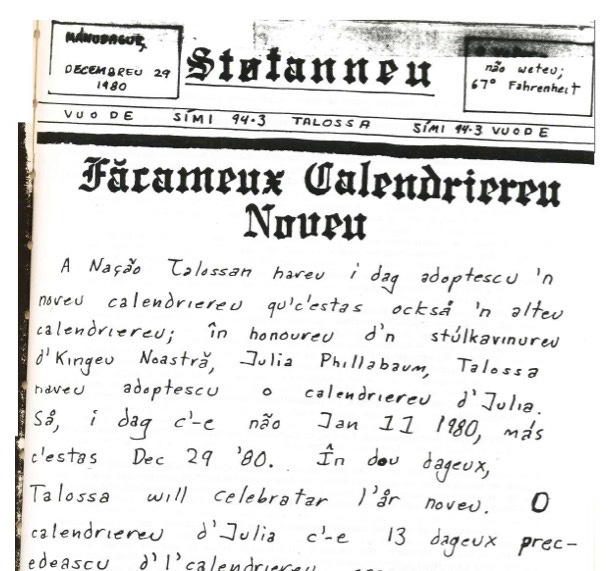

By summer break of 1980, Ben put his invented language to prolific use in Støtanneu, an official newspaper for Talossa with a publisher, editor, and contributor of one. In early issues, Ben declared the latest ABBA single the new Talossan national anthem, he overthrew himself multiple times, and reported on inner turmoil in dramatic headlines like, “Social Upheaval Stuns Talossa!”

Sophomore year was different. Ben befriended other like-minded outsiders, who shunned the “sports-infested youth” of high school to pursue experiments in sovereignty. At an afterschool knighthood ceremony, King Robert I made his new friends honorary citizens of Talossa.

Unsurprisingly, once Ben allowed settlers into his imaginary nation, there were problems. One fellow sophomore in the group, John Jahn, was the loudest and brashest citizen of Talossa. At the time, Ben described him as “a raving Nazi racist whose amicable character saved him from total condemnation.” In heated debates, Jahn became the fascist foil to Ben’s liberal utopianism.

Jahn launched a competing conservative newspaper, The Talossan National News (TNN), which had SS-inspired illustrations of Eagles on the cover. He filled its pages with tirades about “bleeding heart liberals and sexual deviants.” Then, to all of Talossans’ surprise, Jahn came out of the closet. Gayness apparently softened him, and extremism in the kingdom quieted for a while.

Ben’s friends went off to college, but he stayed in Talossa and enrolled at the University of Wisconsin Milwaukee, where his father was a psychology professor. He recruited a new generation of classmates and co-conspirators (plus two of his former high school English teachers) to form a loose confederation. They declared Abbavilla (otherwise known as the UWM campus) their capital, and in 1984 free democratic elections were held. Through a functional parliamentary process, Talossans passed laws and resolutions, negotiated treaties, and even established holidays. It was an unprecedented “counter country.”

A decade passed— the space shuttle Challenger exploded, there was the Iran-Contra Affair, the Simpsons, the fall of the Berlin Wall, Nintendo, Operation Desert Storm, and the siege of Waco. Ben got married. Then in 1996, he launched www.talossa.com

Chris Collins, a 14-year-old Esperanto enthusiast from Virginia, was the first to apply online for citizenship. He was naturalized as Talossa’s first “cybercit.” But when the early web browser Netscape put Talossa’s homepage on their list of the world’s most interesting websites, Ben was inundated with requests. Talossa faced an immigration conundrum— maintain a cloistered community of Milwaukee nerds, or expand globally.

That year hundreds of new micronations started popping up across the web. In an article about the growing movement, The New York Times said, “Many imaginary states are the creations of closet despots nostalgic for the Roman Empire and various Balkan fiefdoms. It's no surprise, then, that many quickly disintegrate or fall victim to coups.” Talossa was unique in its coherence as a nation with over a decade of laws, literature, and customs. As a result, people from around the world wanted to invändrar (Talossan for immigrate), and the process became competitive and increasingly contentious.

Prospective Talossan cybercits were required to purchase at least 2 of the 16 Talossan books for sale on the website, pass a test on Talossan history, and write an essay titled “What Talossa Means to Me.” The kingdom was now a robust online community with 60 citizens hailing from places as far flung as Norway and Brazil. Like most contemporaneous micronations, Talossa was overwhelmingly white and male. Only three of the new citizens were women.

There had always been a 1960s countercultural ethos to Ben’s project; a wish to dropout from the established order and to start anew. Yet a nationalistic cult of personality was equally at play. Most utopian projects inherit the first world problems they hope to transform. More often than not, they disintegrate because of the megalomania of a patriarchal visionary, and Ben was no exception. In Wired he said:

I’ve always been fascinated with dictators… their posturing and flair for public spectacle. There's something about that image - the man in a uniform issuing proclamations to the assembled masses from a balcony. I'm doing basically the same thing - taking normal events and giving them this pompous ballyhooing. It's just a way of feeling that what you do means something.

Ben, of course, was not the first nerd to grapple with power in the project of online world building. Fred Turner’s book From Counterculture to Cyberculture draws the connection between 1960s hippie idealism and ‘90s dot-com neoliberalism through the figure of Steward Brand. In the 1960s, Brand founded the influential Whole Earth Catalog, and through its popularity launched a pioneering Internet bulletin board service called the WELL. On the WELL, outlier visionaries (a few of whom became leading tech company founders) discoursed passionately about the potential for technology and transformation. A group of them created Wired magazine.

In the 1990s, the editors of Wired said technology “would tear down hierarchies, undermine the sorts of corporations and governments that had spawned them,” and replace them with a “peer-to-peer, collaborative society, interlinked by invisible currents of energy and information.” Obviously things didn’t go that way.

As Talossa expanded across the web, its cybercits became increasingly antagonistic. New international citizens were contemptuous of “old growth” Talossans, who fondly recalled the kingdom from Ben’s bedroom. An agitated ruling party came to power, and they contested the kingdom’s standing immigration policies. Anybody who disagreed with them was deemed “unpatriotic.” Ben said in Vice, “Cybercits accused me of 'controlling' any pre-internet citizen who didn't vote for their political parties. 'Ben' became a symbol of tyranny and even 'brainwashing' simply because I spoke for the majority."

The next year, Talossa’s webmasters went rogue. They established a competing nation called Taloosa Republic, and swept up a variety of Talossa-related web addresses. Ben says that he and his family received verbal threats; his computer was targeted by malicious hackers.

The original group of friends who built The Kingdom of Talossa were exacerbated by the authoritarianism that took hold of their nation, and they relinquished immigration duties to someone Ben now characterizes as a “failed businessman from Wisconsin.” The Immigration Minister naturalized his own friends and family, and the original population of Talossa was exiled.

Ben poignantly remembers this all as, “the single most traumatic experience of my entire life—worse than a death in the family and worse than a divorce.” In August of 2005, he abdicated.

In a last ditch attempt to maintain ties to his imaginary world, Ben proclaimed his 8-year-old grandson (aka Prince Louis Adam) to be King. A year later, the fourth grader’s mother pulled the plug because she didn’t like a bunch of grown men talking about her child online.

Talossa, as Ben had dreamed of it, was dead.

Talossa is still going strong today with some 157 citizens active online. Ben has little involvement with the nation he founded, but he’s at peace about it now. On the 30th anniversary of the kingdom, he filmed himself addressing its citizens in front of his childhood home. He said:

For 12 years, Talossa has watched bizarre online groups erupting in opposition to it… Our pride is not in what someone copied, or what anyone stole. It is in what you and I have all been building together since 1979… Today, the ethic of our state is to never allow political disagreements to break up our friendships or our Talossa.

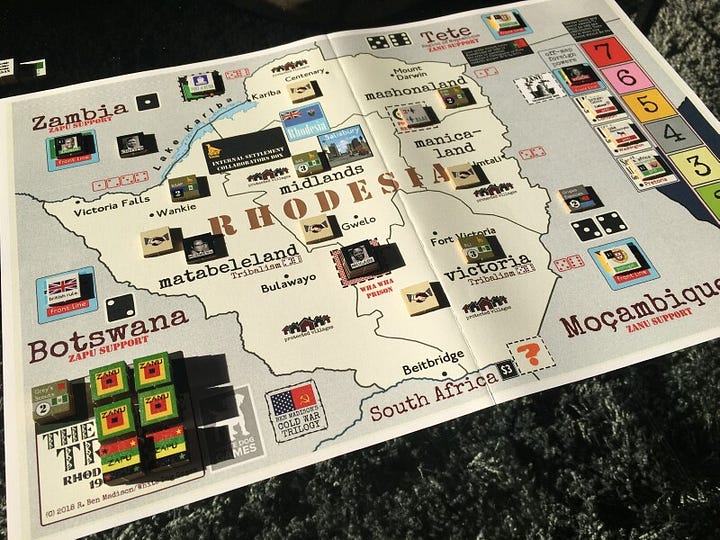

For the past decade, Ben has worked for a florist in Milwaukee as a delivery driver. He’s also a prolific wargame designer. One of his most acclaimed works White Tribe: Rhodesia 1966-1980 is a solitaire-style game where the player represents the white government of Rhodesia, besieged by a black guerrilla army. The aim of the game is to use your armed forces to hold the rebellion back, while persuading colonialist voters to compromise and adopt a black majority rule.

A reviewer of the game reflects, “Despite what some professional policy makers will have you believe, games are terrible at answering difficult questions with nuance. The intricacies of human fragility, emotion, and conflict are poorly served by mechanics that demand that you move a piece here, and flip a counter there. Free a prisoner or shoot a hostage, it’s all just a procedural task.”

Last year a gamer on reddit wrote about Ben’s White Dog Games company: “It is interesting that he made a bunch of games where you play as the bad guys of history.” In other user forums there’s discussion about Ben being banned after allegedly making an Islamaphobic comment to a critic of his game The First Jihad.

Back when 14-year-old Ben was conceptualizing his kingdom, he was newly grieving his mother. Perhaps it’s no coincidence that Ben’s dream of retreating to an imaginary nation-state, where he felt a coherent sense of identity and belonging was born from trauma. That project worked beautifully for Ben, and then it didn’t.

In Ben’s magnum opus Ár Päts ("Our Country") he writes, “Unethical people, for reasons I can’t explain, are attracted to Talossa in disproportionate numbers.” He continues, “What is it that makes Talossa such a bad and unappreciative community? Why are the wicked and angry drawn to it? Is there something about micronations that attracts sickos? Or is it the Internet, where as Pete Hottelet put it, ‘The most tenacious dickhead gets to set the rules?’”

Perhaps the ultimate failure of Ben’s nation-state—with it’s global expansion, white male fiefdoms, immigration culture wars, and monarchic cult of personality—is that it became too real. Ben said, “Its website once touted Talossa as a country small enough for your voice to be heard, yet large enough for that voice to make a real difference. But it failed to live up to its dream.”

This narrative yearns to be a Matt Wolf short documentary. It speaks to larger issues, neurodiversity, nation-building, power, etc, etc. The downside: it could eat up your life, enchaining you to a cognitive rabbit hole.

Incredible narrative. And of course, this would be a magnificent documentary.