Input

My Book of Television Images

A few years ago, I made a film called Recorder about an activist named Marion Stokes, who recorded television 24 hours a day for 30 years. Marion started recording on multiple networks in 1979 during the Iranian Hostage Crisis (considered the birth of the 24 hour news cycle), and she continued until her death in 2012. In the end, Marion amassed 30,000 VHS tapes and an unprecedented archive of the media. My film tells her unexpected life story.

I make films with big archives, and over the years, I’ve developed a specific process to deal with hundreds of hours of footage. The analogy I use to describe what I do is blowing up an enormous boulder of an idea into thousands of little pieces. My collaborators and I methodically organize the pieces, so that we know where to find things. Then an editor begins rebuilding the bolder into a story with a unique shape and style.

My process to make Recorder was particularly elaborate. Marion diligently made handwritten notes with the dates, times, and networks on the spines of her VHS or Betamax tapes. When her son Michael Metelits and her trusted secretary Frank Heilman (two central subjects in my film) began the onerous task of posthumously organizing Marion’s collection, they stored her tapes in thousands of cardboard file boxes.

Michael and Frank didn’t know if anybody would take the tapes (they were being held in a parking lot full of storage pods), and they feared that Marion’s life’s work would be thrown away. Then remarkably, in 2013, the Internet Archive acquired Marion’s collection. The storage pods were shipped from Philadelphia to the Internet Archive’s enormous warehouse in Richmond, California.

What the film’s producer Kyle Martin and I did next goes beyond the typical purview of documentary filmmaking. The Internet Archive didn’t have the resources to “index” Marion’s collection, so we set out to do it ourselves. I put out a call for volunteers on social media, and remarkably, the post went viral. Over 50 people from around the world responded, and they agreed to help organize Marion’s tapes because they were intrigued by her mission and story. In collaboration with the archivist Trevor von Stein at the Internet Archive, we created a unique conveyer belt system with a digital camera mounted above. A crew pushed each file box, filled with Marion’s tapes, down the line, and captured high resolution images of the VHS spines. Zooming into the images allowed us to read Marion’s meticulous logging, and to identify the content on each tape.

Then came the volunteers. Using a shared dropbox folder and google spreadsheet, we assigned images of the VHS spines to transcribers, who entered the “meta-data” from each tape into our database. There was even a logging party at a media arts center in Buffalo. We ended up hiring one of our best volunteers, Katrina Dixon, to be the film’s long-term supervising archivist. She finished the logging process, and put the finishing touches on our crowdsourced finding aid. When librarians hear this story, their eyes pop out of their heads.

My next task was to create a wish list of dates to pull selections from Marion’s 30,000 tapes. Fortunately, Wikipedia has a series of pages that summarize each year. These greatest hits include an eclectic list of events—from historic dates like the fall of the Berlin Wall, to esoteric pop culture moments like the collapse of the Miss Universe pageant stage. My wish list incorporated an unusual timeline of these major events and marginal moments from history. I chose things that piqued my curiosity, but I also considered stories that might have intrigued Marion.

Katrina would scour our database to find a tape from the approximate date and time of the selected event. Then warehouse employees at the Internet Archive would use a forklift to locate the specific pallet with the correct box. Trevor would grab the tapes, and drop them off to our preservationists at Bay Area Video Coalition. Each of Marion’s tapes are 6-8 hours long because she recorded in extended play (Marion never watched her tapes back; she was focused solely on archiving). The preservationists, on the other hand, watched the transfers playback in real time to quality control the image and sound on the degrading analog cassettes. In total, we transferred 100 tapes for approximately 700 hours of footage.

I worked closely with a team of assistant editors to organize the overwhelming volume of material. Sometimes we hit the jackpot with incredible footage, and other times a tape was a dud. I realized that the most interesting material wasn’t the historical events I was looking for, but instead the random local news stories, commercials, or talk shows that intersected with Marion’s life story. After marking my selects, assistant editors organized the material by topics and dates. Then my editor Keiko Deguchi got to work, crafting an unconventional timeline that parallels Marion’s story, and shows how television shapes history.

Looking back, I can’t believe that Kyle and I did all of that. We made a commitment to tell Marion’s story, and as we got deeper into making the film, we did what was necessary to follow through. When you’re in the thick of a project, it’s easy to normalize a process that, in retrospect, seems extreme. As I get older, I wonder if I’ll still be willing to do anything to get a film made. Probably not, but when we were making Recorder, figuring out how to probe this archive felt like a great adventure.

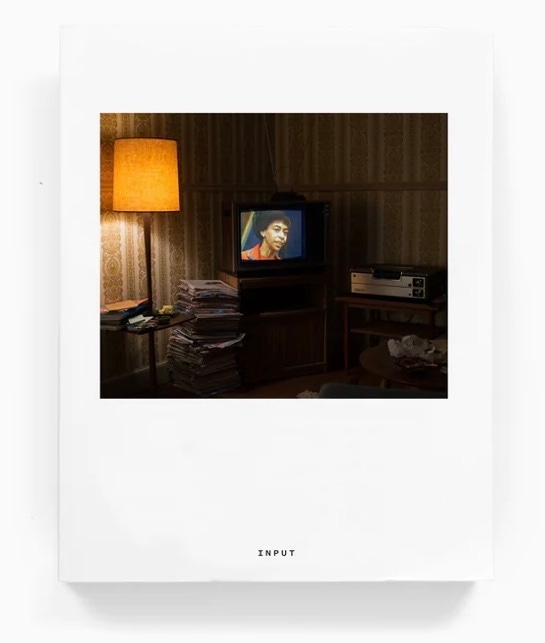

As I was scrubbing through all 700 hours of these tapes, I started to pull still images. I didn’t know what I would do with those images, but I thought of it as a special project. I chose frame grabs that were mysterious, haunting, bizarre, and beautiful. A lot of my filmmaking process is cerebral and story-driven. Pulling these images allowed me to think abstractly, and to save pieces of media detritus from the trashcan of history.

I’m so excited to be releasing a book of these images called Input, named after the public affairs talk show, which Marion co-produced and hosted in the late 1960s. I hope you have an opportunity to watch the film because it’s my favorite that I’ve made (don’t tell the others). That said, the book tells a very different visual story.

I’m so grateful for my friend Matt Connors, who is publishing the book through his Pre-Echo Press. Matt has made some of the most beautiful and thoughtful artist books, catalogs, and records of recent years. He is also an amazing painter, and a fountain of knowledge and cultural references. We are lucky to have collaborated with the talented designer Ben Tousley, and to benefit from the production expertise of Grant Schofield at Pre-Echo. It’s a beautiful object that I think you’ll enjoy.

Below is a preview animation of the book, and I hope you’ll pre-order a copy today. It’s 214 pages of images with an essay by me, and the book ships in November (good holiday gift). More news to come about a book release event and special edition print this fall in New York.

Matt, you know how important this film is to me. I'm ecstatic.

I am so happy about this news!! WOW!! Congratulations! xx